Gambia on Wednesday marked 50 years since gaining independence from Britain. But critics say the anniversary is being tainted by allegations of human rights abuses committed by Yahya Jammeh’s regime.

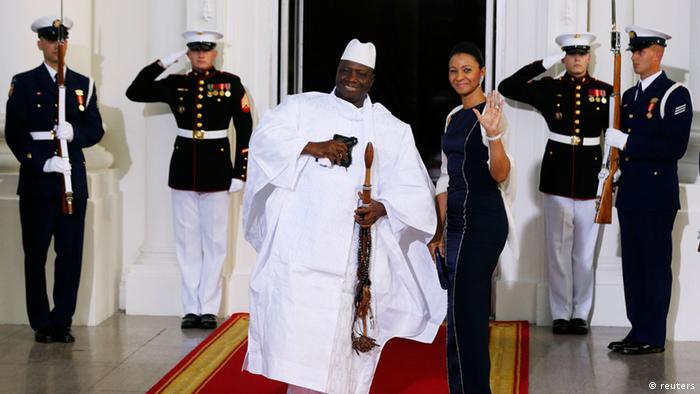

President Yahya Jammeh has ruled the Gambia since seizing power in 1994. His leadership has been marred by controversy and accusations of human rights violations which include enforced disappearances, torture and muzzling of the press.

DW spoke to Francois Patuel, Amnesty International West Africa Researcher

DW: How secure is President Jammeh’s hold on power in Gambia?

Francois Patuel: Definitely what has been happening in the last few years, President Jammeh has created a climate of fear. He has restricted the right to freedom of expression and so he has really secured his power. As soon as you express any dissent in Gambia, you face reprisals from the law enforcement agencies. This is manifested in the laws that were passed in 2013 which include some very broad clauses such as providing false information to a public servant or broadcasting false information. The laws are not clearly defined and are used to target people who show dissent.

Once this legal framework is in place, it’s very easy for law enforcement agencies to arrest anyone who expresses dissent, charge them under those very vague laws or not charge them at all. Gambia’s National Intelligence Agency (NIA) arrests people and very often they don’t charge them until several days in detention and after they have faced torture. The hold on power by President Jammeh is strengthened by the rule of fear and maintained by the closing down of space for people who express dissent.

There was an attempted coup against him in late December. Does this signify widespread discontent with his regime?

It is very hard to tell because no one can really speak out in the Gambia. This has been a major issue for several years. We have received several people at Amnesty International who come to our office after fleeing Gambia, they tell us about the torture they sustained: being electrified and beaten by the NIA. The fact that you can’t express dissent makes it difficult to judge if there is massive discontent. However, the fact that there have been at least 10 attempted coups ever since Jammeh came to power would suggest that there is something wrong in the country. Once people want to have political change they [Jammeh’s regime] feel that they have to revert force – which they shouldn’t have to. It should be that there is political freedom and that space to express dissent.

On this 50th independence anniversary are there any grounds for optimism that the country’s poor human rights record might be about to improve?

We hope that the situation will improve. This is what we have been yearning for over the years. Something that we want to see is the change in the political direction by Gambian authorities to make sure that they respect and protect the rights of their citizens. There would be no better way to celebrate 50 years of independence than ensuring that people can freely celebrate in the streets. What every country and every people aspires to when they become independent is the ability to express themselves freely about their political aspirations and about any policy that the government may take. The problem is that this hasn’t happened in the Gambia. There is a crackdown on dissent which has been ongoing since 2006 which was the last time a major coup attempt took place.

States in the region, particularly those which will be going to the Gambia to celebrate its independence should be questioning government authorities on the deterioration of human rights record. They ought to make key recommendations to the Gambia such as removing laws which are meant to restrict freedom of expression, ending secret detentions and implementing the decisions of the ECOWAS community court of justice or the African Commission resolutions on the Gambia. It is very important because Gambia, a small country, cannot continue to act as it does and be an affront to the human rights machinery at the international and regional level.