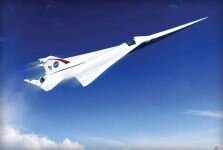

Illegal immigrants from Burma and Bangladesh arrive at the Langkawi police station’s multi-purpose hall in Malaysia. Photograph: Hamzah Osman/AP

A crisis involving boatloads of Rohingya and Bangladeshi migrants stranded at sea has deepened as Malaysia said it would turn away any more of the vessels unless they were sinking.

The waters around Malaysia’s Langkawi island – where several crowded, wooden vessels have landed in recent days carrying more than 1,000 men, women and children – would be patrolled 24 hours a day by eight ships, said Tan Kok Kwee, first admiral of Malaysia’s maritime enforcement agency.

“We won’t let any foreign boats come in,” Tan said on Tuesday. If the boats are sinking, they would rescue them, but if the boat are found to be seaworthy, the agency will provide “provisions and send them away”, he said.

South-east Asia is in the grips of a spiralling humanitarian crisis as boats packed with Rohingya and Bangladeshis are being washed ashore, some after being stranded at sea for more than two months.

As many as 6,000 asylum seekers are feared to be trapped at sea in crowded, wooden boats, and activists warn of potentially dangerous conditions as food and clean water runs low.

The crisis appears to have been triggered by a regional crackdown on human traffickers, who have refused to take people to shore. It reached a tipping point this weekend, when some captains and smugglers abandoned their ships, leaving migrants to fend for themselves.

One boat sent out a distress signal, with migrants saying they had been without food and water for three days, according to Chris Lewa, director of the nonprofit Arakan Project, who spoke by phone to people on the boat.

“They asked to be urgently rescued,” she said, adding there were an estimated 350 people on board, and that they had no fuel.

In the last three days, the 1,158 people landed on Langkawi island, according to Malaysian authorities, and 600 others in Indonesia’s westernmost province of Aceh. With thousands more believed to be trapped in vessels at sea, that number is expected to climb, said Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division.

Malaysia’s announcement comes a day after Indonesia also turned back a ship, giving those on board rice, noodles, water and directions to go to Malaysia.

The migrants aboard the boat that sent a distress signal described an approaching white vessel with flashing lights while she was on the phone, Lewa said. One minute they were cheering because they thought they were about to get help, she said, and the next they were screaming as the boat moved away.

“I can hear the children crying, I can hear them crying,” she said.

Lewa has tracked about 6,000 Rohingya and Bangladeshis who have boarded large and small trafficking boats in the region in recent months, but have yet to disembark. Based on her information, she believes the migrants and the boats are still in the Malacca strait and nearby international waters.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the US, Australia and other governments and international organisations, meanwhile, have held a string of emergency meetings to discuss possible next steps.

They are worried about deaths, but also the looming refugee problem. In the past, most countries have been unwilling to accept Rohingya, a Muslim minority from Burma who are effectively stateless. They worry that by opening their doors to a few, they will be unable to stem the flood of poor, uneducated migrants.

Malaysia’s home ministry said in a statement that of the 1,158 people who landed on Sunday on Langkawi island, 486 were Burmese citizens and 672 were Bangladeshis. There were 993 men, 104 women and 61 children.

A government doctor said many survivors were being treated for diarrhea, abdominal pains, dehydration and urination problems.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations – a regional group that brings together all of the main stakeholders, from Burma and Thailand to Indonesia and Malaysia– has a strict stance of non-interference in member affairs.

At annual Asean meetings – the most recent, ironically, on Langkawi – Burma has blocked all discussion about its 1.3 million Rohingya, insisting they are illegal settlers from Bangladesh even though many of their families arrived generations ago.

For most part, member countries have agreed to leave it at that.

Labeled by the UN one of the world’s most persecuted minorities, the Rohingya have for decades suffered from state-sanctioned discrimination in the Buddhist-majority Burma, where they have limited access to education and adequate healthcare.

In the last three years, attacks by Buddhist mobs have left 280 people dead and forced 140,000 others from their homes. They now live under apartheid-like conditions in crowded camps just outside the Rakhine state capital, Sittwe.